Building an HTTP/2 server in C++ and hosting my site with it

Contents

- Contents

- Background

- Development process

- Container & Executable Hardening

- HTTP/2 Attacks

- Cloud Provider Options

- Summary

- Bonus Content: Memory Leak

Background

I wanted to learn more about HTTP/2 and also have a go with C++23, so I decided to build an HTTP/2 server from scratch, referencing the RFC as the primary source of information. It has been a really fun project so far but what better test than to throw it to the internet wolves and dog food it with my personal site? Whilst my site is not exactly an ocean of content, proving out the server against real traffic and contemplating things that can go wrong (including by innocent and nefarious actors) made for some interesting learnings about how to protect intrinsically unsafe applications against attack. Unsafe, because it is handling external input from the world, but also it’s C++ and fundamentally unsafe from a memory perspective.

Inevitably you are probably wondering, why didn’t I write it in Rust? I wanted to learn C++ for audio development but it is likely I’ll learn Rust too at some point. I also think that coming from C++ will help me understand Rust better!

Development process

I followed lean principles and TDD to develop Ion. Starting with very basic functionality (return :status: 200 given any HTTP request) and then building up functionality. Whilst the server is written in C++, I developed system-level tests in Python, and verified the server against standard HTTP/2 clients, starting with curl then moving onto Python-based HTTP/2 clients to test more specific functionality (specifically h2hyper, httpx). For benchmarking and testing concurrency I used h2load from nghttp2. Eventually my server had a fairly basic, but extensible base for serving requests:

#include "ion/http2_server.h"

int main() {

ion::Http2Server server{};

auto& router = server.router();

router.add_route("/", "GET", [](const ion::HttpRequest&) {

const std::string body_text = "hello";

const std::vector<uint8_t> body_bytes(body_text.begin(), body_text.end());

return ion::HttpResponse{

.status_code = 200,

.body = body_bytes,

.headers = content-type};

});

server.start(8443);

return 0;

}

But these artificial tests were only going to push development so far. I wanted to test against browsers and whatever proxy Google, Cloudflare and others would eventually front the server. For this, I decided I would build everything needed to host my own personal site landing page and content. This involved adding static file support, so I could bundle my site into whatever environment I found that would host my humble site.

Before throwing the server to the wolves, I also spent time hardening the HTTP/2 server logic, the binary produced and the container image.

Container & Executable Hardening

I wanted to containerise the server as this would provide significant advantages in terms of security and deployability. Most cloud providers have some container hosting facility, and in particular I was interested in serverless options, mostly as it would be the simplest option. I also didn’t want to manage the OS myself given the high-risk payload I was running. Cloud providers are already very good at sandboxing containerised workloads via micro-VMs with Kata Containers, or Linux kernel emulation in user-space options like gVisor. Whilst that covers kernel vulnerabilities, I also had to deal with the possibility of remote code execution and generally doing bad stuff within the container.

Given the risks I employed the following methods to reduce the security blast radius:

1. Run as non-root user within container

A pretty obvious safety measure which any container workload should really be using. It reduces the likelihood of escaping the container as well as being less likely to be able to exploit kernel flaws.

USER ion

2. Use scratch as a base image

All Ion requires to run is its executable, the content it is going to serve and also any library binaries it needs to run (i.e. OpenSSL, libc++ etc). Basing the server image on scratch provides a completely empty filesystem. No shell, no /bin, no /lib. Only what you selectively want to add. This has a tremendous impact on what an attack can actually do even if they gain the ability to execve within the container. Try executing without any executables around!

One downside however is that using scratch renders docker image vulnerability scanning tools such as those included in Google Artifact Repository (GAR) unable to recognise included packages. Essentially as it cannot detect the Linux distribution & package manager used, because it isn’t really a distribution, just raw binaries. As a workaround, the build stage can itself be pushed to GAR. It can then scan that image since the included libraries ultimately are sourced from that.

In order to know what to copy into the container image, I took the approach of using the output of ldd build/app/ion-server to dynamically pull in the dependencies required to the new root filesystem. For example, on the ARM64 build of Debian, ldd outputted:

linux-vdso.so.1 (0x0000e4f3b8db6000)

libc++abi.so.1 => /lib/aarch64-linux-gnu/libc++abi.so.1 (0x0000e4f3b8c10000)

libssl.so.3 => /lib/aarch64-linux-gnu/libssl.so.3 (0x0000e4f3b8b40000)

libcrypto.so.3 => /lib/aarch64-linux-gnu/libcrypto.so.3 (0x0000e4f3b8600000)

libc++.so.1 => /lib/aarch64-linux-gnu/libc++.so.1 (0x0000e4f3b84e0000)

libunwind.so.1 => /lib/aarch64-linux-gnu/libunwind.so.1 (0x0000e4f3b8b10000)

libm.so.6 => /lib/aarch64-linux-gnu/libm.so.6 (0x0000e4f3b8430000)

libgcc_s.so.1 => /lib/aarch64-linux-gnu/libgcc_s.so.1 (0x0000e4f3b8ad0000)

libc.so.6 => /lib/aarch64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6 (0x0000e4f3b8270000)

/lib/ld-linux-aarch64.so.1 (0x0000e4f3b8d79000)

Here’s the relevant section of app.Dockerfile:

# ... application compiled in build/app/

RUN mkdir -p /runtime-root/etc /runtime-root/lib /runtime-root/usr/lib \

/runtime-root/app

RUN ldd build/app/ion-server | grep "=>" \

| awk '{print $3}' \

| xargs -r cp -L --parents -t /runtime-root/

RUN ldd build/app/ion-server | grep -v "=>" \

| grep -v "linux-vdso" \

| awk '{print $1}' \

| xargs -r cp -L --parents -t /runtime-root/

RUN cp /etc/ssl/certs/ca-certificates.crt /runtime-root/etc/

RUN echo "ion:x:1000:1000:ion:/app:/usr/sbin/nologin" > /runtime-root/etc/passwd

RUN echo "ion:x:1000:" > /runtime-root/etc/group

RUN cp build/app/ion-server /runtime-root/app/ion-server

FROM scratch

COPY --from=builder /runtime-root /

USER ion

WORKDIR /app

EXPOSE 8443

ENTRYPOINT ["/app/ion-server"]

3. Prevent unintentional process escalation with PR_SET_NO_NEW_PRIVS

Whilst we’ve removed other binaries from the container image such as sudo and other setuid targets, it doesn’t hurt to prevent the kernel from elevating the process’s privileges (or that of child processes), past what was initially granted.

To do so, the following code was used to prevent any new privileges from being granted:

bool ProcessControl::enable_no_new_privs() {

#ifdef __linux__

if (prctl(PR_SET_NO_NEW_PRIVS, 1, 0, 0, 0) == -1) {

spdlog::warn("failed to set PR_SET_NO_NEW_PRIVS: {}", std::strerror(errno));

return false;

}

spdlog::debug("PR_SET_NO_NEW_PRIVS enabled");

return true;

#else

return false;

#endif

}

4. Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR) & read-only Global Offset Tables (GOT)

ASLR causes the location of symbols to be unpredictable each run of a process and thus infeasible to “jump to” should an attack obtain the ability to perform remote code execution within a process. It’s enabled by default in macOS and is optionally enabled when compiling for Linux. Whilst it makes guessing symbol addresses difficult, an information leak (such as some code from a library) can be used to work out where such a library is located and thus give clues to the attack as to where they should jump to should they want to jump into a library’s procedure. The location of the stack or heap can also be exposed this way. It is enabled via the -fPIE compiler flag and the -pie linker flag.

The GOT contains function pointers used for dynamic linking. It can be made read-only, preventing attacks which overwrite table entries (for example, swapping puts for system). This method is typically used in tandem with ASLR to harden the binary against remote code execution vulnerabilities. It is enabled with the -z,relro & -z,now linker flags (see CMakeLists.txt):

target_compile_options(ion-server PRIVATE -fPIE)

if (NOT APPLE)

target_link_options(ion-server PRIVATE

-pie

"LINKER:-z,relro"

"LINKER:-z,now"

)

endif ()

5. Strip symbols from binary

Ensuring symbol debug information is not included in the binary makes it harder (although not impossible) to reverse engineer what the loaded program is doing. Ultimately, since ion is open source, anyone can reproduce the compiled binary but it’s good hygiene to strip the symbols from released binaries nonetheless.

HTTP/2 Attacks

Now it’s all well and good building a web server for the learning, but such pursuits typically don’t have defensive coding high up on the priority list! That said, whilst I am sure I have not protected the server against all known HTTP/2 vulnerabilities, I have taken some measures to ensure that some of the more obvious protocol abuses are prevented. Additionally, because it is ultimately fronted by a CDN, I am able to take some solace from the fact that the CDN will also provide some protection.

Some of the measures I have taken are:

- Ensuring connections are timed out if TLS handshaking, HTTP/2 preface and data transfer does not occur rapidly. I also employed an idle connection reaper to close connections that have not sent or received data via

epollorpollafter a certain period of time. - Hard limiting HTTP/2 frame size to 16 KB.

- Limiting the size of the HPACK dynamic tables to 64 KB.

- Limiting the read buffer size to 256 KB.

- Limiting string sizes used in header names & values to 4 KB.

- Limiting the number of bytes that are read during the decoding of integers. Technically the integer representation mechanism described in RFC 7541 allows an attacker to send a continuing stream of zeros, which won’t overflow the resulting integer, and will just eat away at the server’s CPU until another limit (such as frame size) is hit.

- Hard limit the number of concurrent connections to 128; and drop subsequent incoming connections. I’ve no doubt the server can certainly handle more, but for the purposes of hosting my site behind a CDN, 128 is more than enough for now!

Cloud Provider Options

Cloudflare

Cloudflare offers the ability to run containers as part of their Workers offering. It’s possible to forward all HTTP traffic to a container by using the following example Worker code:

import { Container, getContainer, getRandom } from "@cloudflare/containers";

import { Hono } from "hono";

export class MyContainer extends Container<Env> {

defaultPort = 8080;

envVars = {};

}

const app = new Hono<{

Bindings: Env;

}>();

...

// Load balance requests across multiple containers

app.get("/lb", async (c) => {

const container = await getRandom(c.env.MY_CONTAINER, 3);

return await container.fetch(c.req.raw);

});

export default app;

However, the container.fetch() method either doesn’t support requesting via HTTPS and/or also does not support HTTP/2. Ion was erroring at the TLS handshake with an error which indicated the client was attempting a cleartext connection. When I put Ion into h2c mode, Ion complained of an invalid HTTP/2 preface. No go!

In a way this makes sense from a product perspective. Cloudflare Workers allow you to host containers but really as a means of providing an auxiliary service to an already existing web application. As such there’s no direct way of proxying HTTP connections directly to the container (at least by way of Layer 4 proxying).

bunny.net

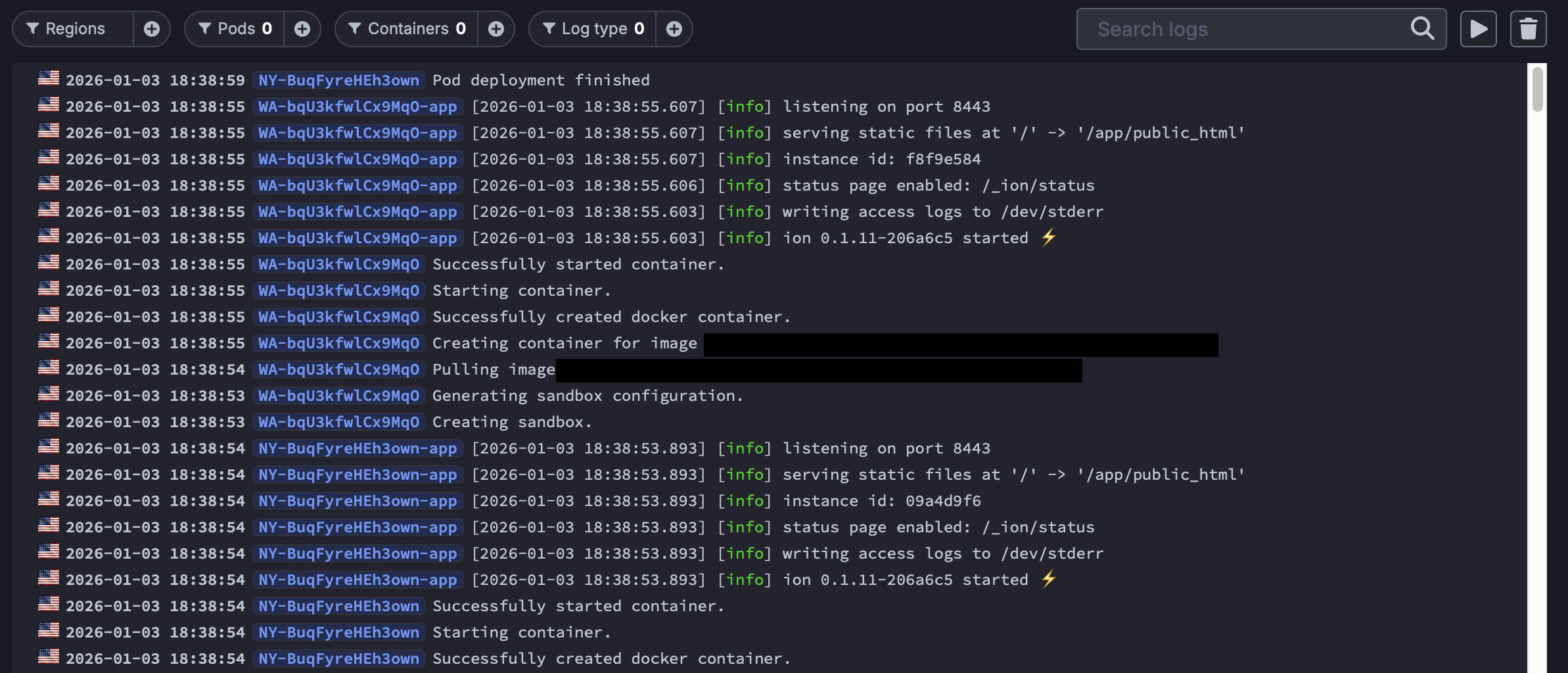

Bunny provides a container hosting service called Magic Containers. They can host and scale a set of containers providing an anycast IP endpoint directly to the container set, or you can front the container fleet with their CDN. The anycast IP endpoint approach worked quite well and their logging platform even supports ANSI colouring! 🤯

I was unable to front the container with their CDN offering and thus had to use Cloudflare as the CDN. It seems Bunny’s frontend doesn’t support origins with HTTP/2. A quick chat with their support team on Discord revealed that indeed at present HTTP/2 to the backend is not yet supported.

Google Cloud Run

GCP provides a serverless solution called Cloud Run which provides a Knative-like interface for hosting containers. It is highly configurable and enables your containers to serve requests via the Google Frontend. Whilst this supports HTTP/1.1, 2 & 3, Cloud Run by default talks HTTP/1.1 between the container and frontend. However, it can be configured to use HTTP/2 instead. The only catch is that it has to be cleartext. TLS is not supported. In fact, before trying Cloud Run, Ion only supported TLS. I had to add h2c support so it would work!

Summary

For now, Ion and my personal site is hosted in bunny.net, with Cloudflare continuing as the frontend to provide HTTP/1.1 support and content caching. You can check out how Ion is getting on by checking out the status page of a lucky server instance.

I could have used Google Cloud to host Ion, but since I work within GCP professionally I wanted to try another provider to expand my repertoire, so I have kept it hosted within bunny.net! And my choice definitely had nothing to do with their cute lagomorphic imagery…

Bonus Content: Memory Leak

It should come as no surprise that I encountered at least one memory leak as part of the development of Ion. But amazingly, it really was only one. Naturally it was when I needed to manage the lifetime of a C-based library.

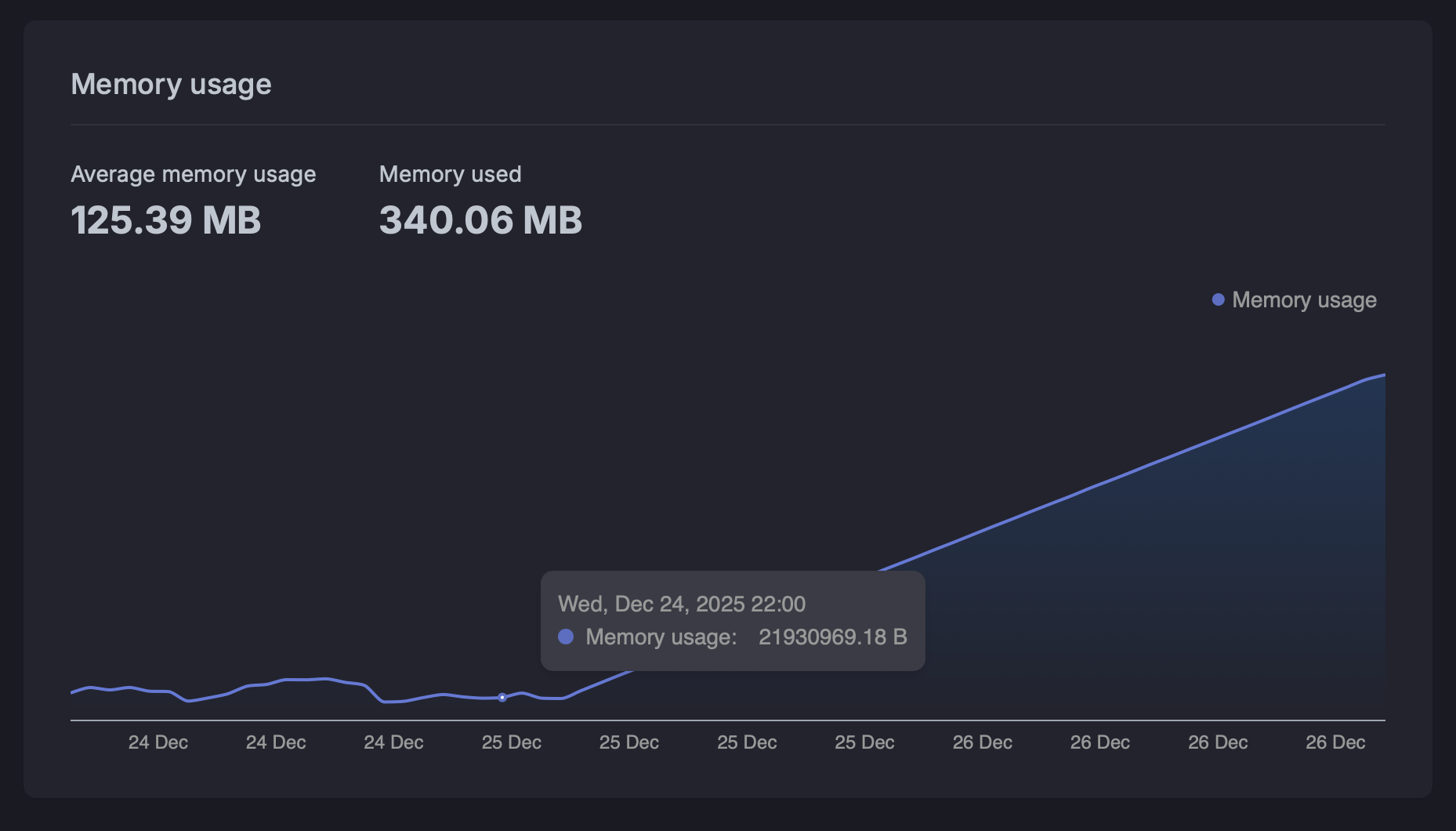

Having embraced modern C++ as much as possible during development, I made heavy use of RAII, references and smart pointers to manage the life of C++ objects. When working with OpenSSL, however, you need to manage the lifecycles of SSL and SSL_CTX objects yourself. It was only a small memory leak, but it was quite visible over a long period:

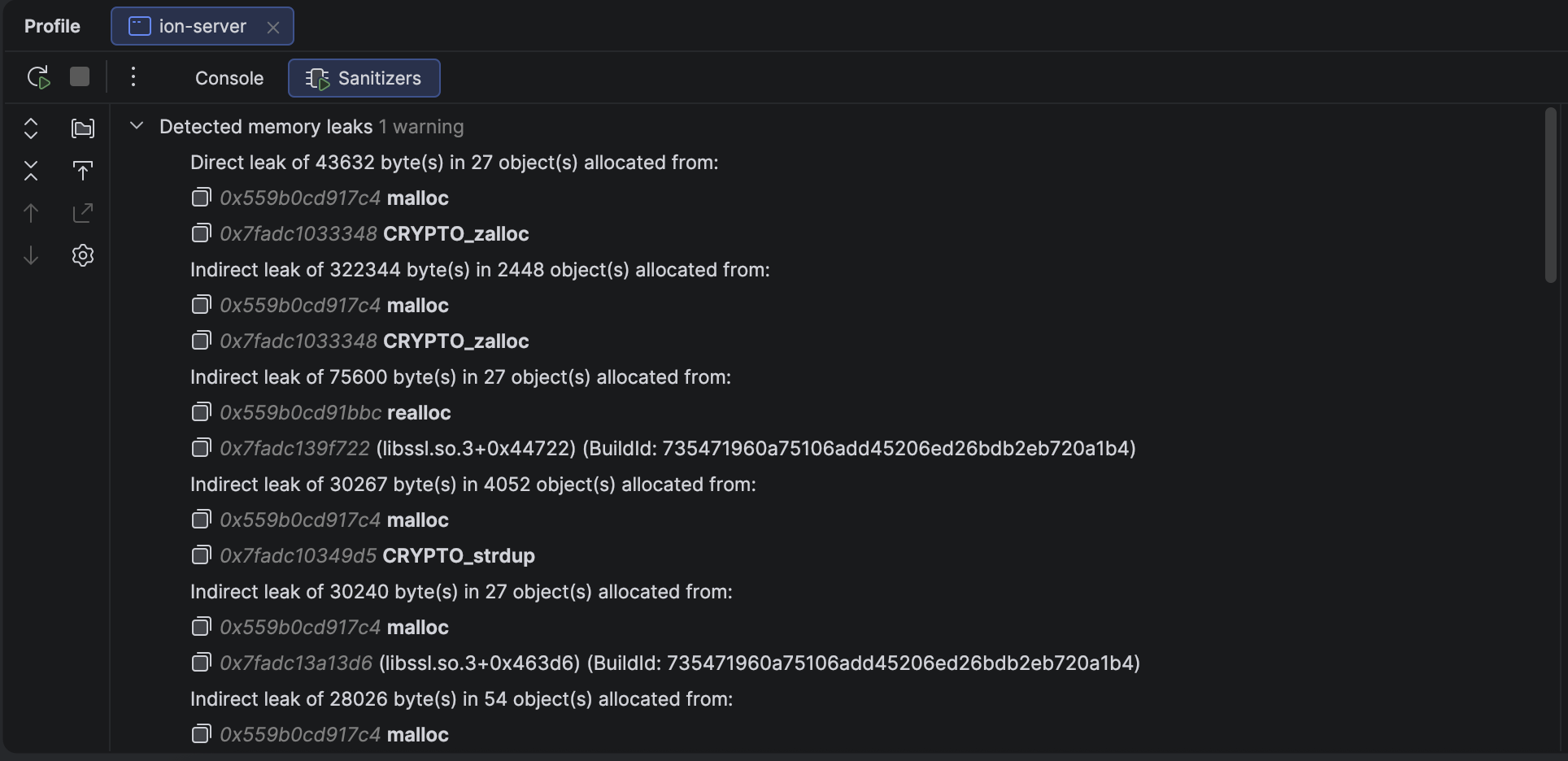

I run debug builds with the address sanitizer enabled in Clang, and LeakSanitizer (LSan) is enabled as part of that:

if (CMAKE_BUILD_TYPE STREQUAL "Debug")

target_compile_options(ion-server PRIVATE

-fsanitize=address

-fno-omit-frame-pointer

-g

)

target_link_options(ion-server PRIVATE

-fsanitize=address

)

...

When running builds within CLion and putting a substantial load through the server using h2load, the LSan results showed there was some leakage:

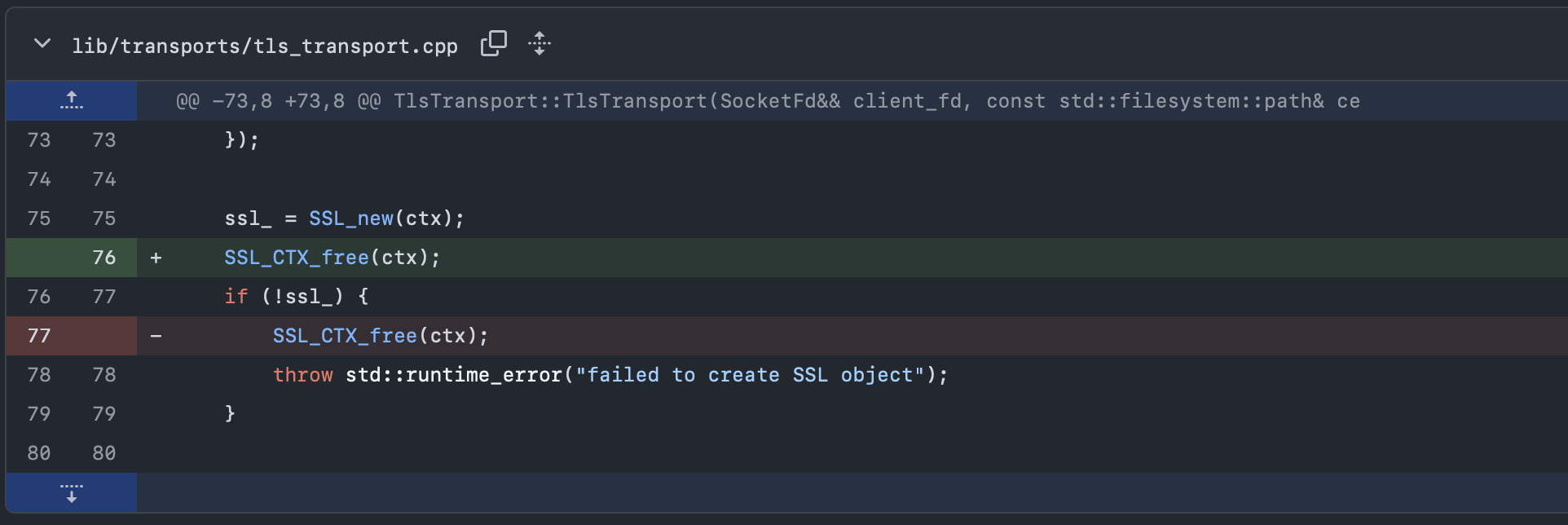

Whilst the output is not explicitly calling out SSL or SSL_CTX, it’s calling out symbols which are part of OpenSSL. I already knew I was mis-using SSL_CTX as I was instantiating an SSL context object for every connection opened. I thought at least I was deleting it correctly as part of the TLS transport destructor, but alas not! The issue was solved in this diff:

It turns out that SSL_CTX should always be freed after an SSL object is newed, not just if there is an error from SSL_new(). Since OpenSSL uses reference counting internally, this ensures that it only counts the reference it then holds as part of the SSL object.

The reason why the memory leak was so smooth as shown in the graph, was that bunny was doing TCP health checks against the container to ensure it was running, and every time a TCP connection was opened and closed regularly, the server was attempting an TLS handshake, which required creating the OpenSSL objects.

Ultimately, the fix was superseded by actually implementing ion::TlsContext which then handled the lifecycle of SSL_CTX correctly and was shared between all TLS connections, as it should have been in the first place!